Video games have been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. One of my earliest memories is of playing Lego Batman before one of my birthday parties. Our Playstation 2 was hooked up to a box TV, which was wedged into a tall wooden armoire in the playroom of my family’s home in Virginia. The round screen flickered with static as I (Batman) explored the Gotham Zoo on the back of a Lego elephant.

Since childhood, video games have been a large part of how I experience play, both on my own and in community. So many of my friendships have been forged in hours spent in front of the TV, collaborating or competing in some imagined task until our eyes hurt. (Don’t worry, we played outside too). Much of my time with friends as a kid was spent passing the Wii remote back and forth while we played games like Mario Kart, Skylanders, and Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga.

As my friends and I grew up, so did the games we would play and the systems we’d play them on. The Wii became an Xbox 360 which became a Playstation 4. Lego Star Wars and Skylanders gave way to Battlefront, Fortnite, and Call of Duty: Black Ops. Alongside these multiplayer arcade-style games, my friends and I would also take turns with single-player narrative-based games like Uncharted, Spider-Man, and The Last of Us. While the content matured and complexified, the fun that we shared remained largely the same and does to this day.

While I have always enjoyed playing video games, I have also found them morally confusing. In most of the games I mention above, violence is a central feature of their gameplay. As a person of Christian faith, I have found it difficult to reconcile how I am called to resist violence in the real world with how it is celebrated in most video games. I have often had to ask myself if it’s wrong for me to enjoy enacting violence in a virtual world and what effect that may have on my heart.

Though gaming took a back seat during my last few years at college, I have enjoyed playing a bit again in this newer, slower season of my life. I played a game this fall that seemed like it was asking similar questions about the morality of violence in video games, which was quite an encouragement. What follows is a review of that game, as well as a reflection on how it has helped me consider what healthy engagement with violent video games might look like for a person of faith.

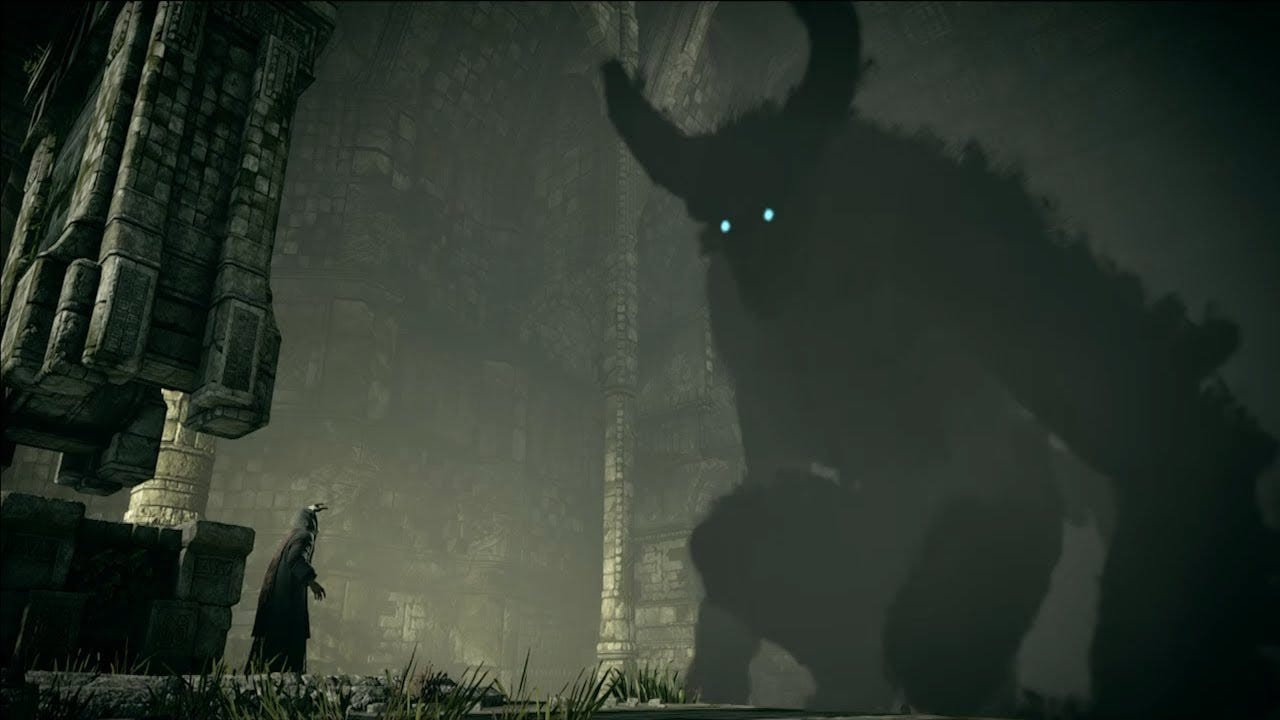

Since its release, The Shadow of The Colossus has been heralded as a profoundly influential video game. Originally released for the Playstation 2 in 2005, it was entirely reconstructed for the Playstation 4 in 2018 (the version I played). Its awe-inspiring visuals, solemn atmosphere, and tragically compelling narrative all contribute to an immersive gaming experience. Like many (if not most) video games, violence is central to Shadow’s gameplay. However, unlike most games I have engaged with, Shadow seems to question the role that violence occupies within itself, both in the experience of playing the game and in the narrative it tells.

The story of The Shadow of The Colossus follows a young man named Wander as he seeks a way to bring his beloved, Mono, back from death. The opening cinematic shows the protagonist traversing harsh landscapes on horseback with the body of his lover lying behind him. His journey ends (and the gameplay begins) as he rides across a long and seemingly ancient bridge that leads to the ruins of a temple. This sequence is breath-taking, giving the player a glimpse of the stunning visual spectacles that await her.

Within the temple, our protagonist calls out to the deity rumored to reside within, one who is said to have the power to raise the dead. This apparent god responds to Wander’s call in an eerie unison of layered voices speaking a fictional language. The voices tell Wander that while this rumor is true, he must complete a task before they will raise his beloved. This task is the slaying of the colossi, sixteen massive beasts that roam the surrounding landscape and correspond to a series of idols that stand within the temple.

And so the game consists of 16 missions in which Wander must find a colossus and discover how to overcome it. With the killing of each colossus, an idol in the temple falls and Wander comes one step closer to being reunited with Mono. Though this may sound repetitive, each level offers a unique blend of wonders and challenges that kept me excited to the very end.

Each level begins with exploration as Wander rides out into the surrounding countryside in search of the next colossus. The fields of rolling hills surrounding the temple give way to towering cliffs, winding caves, dense forests, and sweeping deserts. The path to each colossi takes Wander and the player into a distinct setting within this beautiful and haunting landscape.

The region Wander explores is called the Forbidden Lands, an apt name for how the world of the game is designed. Ruins of temples, shrines, and cities are scattered across the map, but there is little to no visible life apart from Wander, his horse Agro, and the colossi they pursue. The emptiness of the map is one of the more unique elements of Shadow when compared to other open-world games. It communicates a feeling of loneliness (a theme of the game helpfully explored in this NPR article) while also offering a distilled experience in which the story remains in focus.

Beyond the stark beauty of the setting, each colossus is a wonder to behold. The colossi are designed as creatures of stone, moss, fur, and flesh that range from the size of a small car to that of a skyscraper. Some of the colossi are larger than any fixture I can remember seeing in a video game. While many of the colossi resemble certain animals, each design feels original. A favorite of mine is a serpent-like beast the size of a football field that can fly using a set of wings and pouches that inflate like hot air balloons.

What is most wondrous to me about this game is that the colossi are not elements in a backdrop seen only from a distance, but they are characters with whom the player can directly interact. To defeat each colossus, Wander must find a way to climb it and explore its body for vulnerable points. While he climbs, the colossus reacts to his movements and attempts to shake him off. This is a wonderfully overwhelming experience as a player, but one that requires intense focus. Each colossus has a unique pattern of behavior that must be studied for potential openings, making every encounter as much a puzzle as it is combat.

Though it was thrilling to discover how to conquer each colossus, most of my enjoyment came from being able to interact with and explore these massive, mysterious creatures. I even found myself saddened by the fact that I had to kill them to continue the game, wishing that there was a version of the story in which these creatures and I could live together in peace.

But the game must go on, and we must remember that Wander is driven to these dangerous encounters out of a desperate longing to be reunited with his love. And so with each successive colossus killed, we sense our protagonist come closer to his goal. Or so it seems. (What follows contains spoilers for the end of The Shadow of The Colossus. If you find yourself intrigued by the game, go play it and read the rest of this essay after!)

There are hints throughout the game that cast a shadow of doubt on the morality of Wander's mission. When each colossus is killed, a black vapor spews out of its wounds instead of blood. This substance swirls in the air for a moment before rushing into Wander’s body through his eyes, mouth and stomach, causing him to collapse and fall unconscious. He awakes to find himself back in the temple, ready to pursue the next colossus. While this functions as a helpful transition between levels, it also visually communicates a sense of pollution and dehumanization that comes with the violence Wander commits. This leads the player to question the morality of Wander’s actions and her own culpability in them.

There are musical warnings against Wander’s mission as well. The theme associated with the temple involves a foreboding organ motif, and the song played at the death of each colossus is undeniably mournful. These clues among others culminate in the tragic conclusion of The Shadow of The Colossus, in which the violence the game encourages the player to commit is called into question.

After defeating the final colossus, a creature of startling size, the game breaks the pattern of showing Wander awaken in the temple after completing each mission. Instead, a group of masked figures is shown entering the temple. They react in horror upon seeing the fallen idols that represent the now slain colossi. Only after their entrance does Wander appear, but not as he has been seen before. His pallid skin and glowing eyes suggest that he is in torment and out of his mind, and a pair of horns protrude from the sides of his head.

Through the subtitled dialogue between the masked men, the player learns that the deity of the temple goes by the name of Dormin. An evil being defeated long ago, Dormin’s return was held at bay by the fracturing of their spirit into 16 pieces, which are, you guessed it, the colossi. By tricking Wander into killing the colossi, Dormin was preparing the way for their return.

This is meant to take place through Wander’s body, which explains his monstrous appearance. To stop Dormin’s return, the group of horsemen attempt to kill Wander, stabbing him through the heart. Just like the colossi, the sword-dealt wound in Wander’s body spews a black spray into the air. However, the blow doesn’t kill him; it triggers his transformation into Dormin, a shadowy figure the size of a colossus.

For a brief moment, the player gets to play as Dormin, whose movements mirror those of previous colossi. This twist offers a strangely empathetic experience; it puts the player in the place of the beasts she has been killing throughout the game. While a few blows can be landed against the masked men, the game won’t let them be stopped. The masked men succeed in defeating Dormin, just as Wander did in killing the 16 colossi.

The game ends with an extended cinematic that plays underneath the credits. After Dormin's defeat and the seeming death of Wander, there is an extended shot of Mono lying on the altar. What seems to be a final reminder of Wander’s folly becomes a surprising twist of hope: the shot holds to show Mono’s eyes bat open, brought to life again.

As she rises, she begins to look for her lover. She turns to see Agro, Wander’s trusty equine companion (who had appeared to fall to his death in the previous level), hobbling in on a broken leg. Together, they slowly walk towards the place where the body of Wander is likely to lie.

Instead of a dead body or an empty floor, Mono finds a small, crying baby with horns on its head. She lifts the baby and holds it in her arms. Agro looks, turns away, and hobbles up a winding staircase into a sunlit chamber above. The final shot we see of these characters shows Mono holding baby Wander in a courtyard of the temple, bathed in sunlight and surrounded by vegetation and wildlife.

From start to finish, The Shadow of The Colossus surprised me with its treatment of violence. Through its design and its story, it made me feel the weight of the killing it guided me, as the player, to commit. The end of the story affirmed these conflicted feelings, taking seriously the consequences of the violence committed by its protagonist while still leaving open the possibility of redemption and renewal.

My experience of the game also offered flickering glimpses of what it could be like to experience wonder in video games without violence. As I mentioned before, my enjoyment of the game came largely from getting to behold and interact with its wonderful creatures and environments, not in the violence it encouraged. I felt a sense of regret and frustration in having to kill the colossi, which is a far cry from how many other games have made me feel about violent action. This game made me long for a world in which I could befriend these beasts instead of hunting them down.

While this longing casts a vision for engaging, non-violent video games, it also touches on a deeper hope, one that has helped me make sense of my experience of this game as a person of faith. The way Shadow explores the relationship between humans, animals, and violence reminds me of how the prophet Isaiah describes the promise of God’s New Creation in the Old Testament:

The wolf will live with the lamb,

the leopard will lie down with the goat,

the calf and the lion and the yearling together;

and a little child will lead them.

The cow will feed with the bear,

their young will lie down together,

and the lion will eat straw like the ox.

The infant will play near the cobra’s den,

and the young child will put its hand into the viper’s nest.

They will neither harm nor destroy

on all my holy mountain,

for the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the Lord

as the waters cover the sea.1

The coming world for which Christians hope is one in which humans and beasts of all strengths and sizes might live and play together in peace. In that land, there will be no violence, only wonder.

Though The Shadow of The Colossus doesn’t offer an experience of this kind of peace, the final moments of the game gesture toward a similar hope. The player is left with Mono and the now-infant Wander peacefully surrounded by animals of various kinds in a land once void of life. In this image, both the brokenness of the present and the hope of the future are on full display.

Isaiah’s vision of a world without violence is the end of the story that God is writing, but our lives play out in the middle. Like my experience playing The Shadow of The Colossus, life here and now is marked by both wonder and frustration. We marvel at the goodness God has created, we lament the violence that can seem to define our lives, and we wait for a world in which peace will endure.

While we wait for the fulfillment of this future hope, we have work to do in the here and now. We are called to live in a way that bears witness to the truth of God’s coming kingdom of peace and love. As we do so, we can trust that God will use what we do in his greater work of making all things new.

Part of this work, I would argue, is to play, living into imagined stories that attune our hearts to the truer and greater story in which we live. Video games have the potential to be a part of this sort of sanctifying play, if the stories they tell take seriously the actions into which they guide the gamer. The Shadow of the Colossus has been one of those games for me, giving voice to the tension between the world we see and the world for which we hope.

Isaiah 11: 6-9 (NIV)

Cool thoughts Mikey. Just read an NYT article about how creativity in video games might be dead, but you highlighted some points that could resurrect it.

Beautiful thoughts as always Mikey! Thank you for sharing.

Having played the game myself, I was personally fascinated by the scope of the game, something you mentioned being a standout feature. When we talked about it in person, we both made note of the camera moving to angles unfamiliar to most video games, allowing us to feel how small we are compared to the colossi. While reading your article and thinking of the game through an artists view, the scope of the colossi becomes incredibly symbolic of the actions your taking as a player. Being mislead, you are playing a small yet crucial role in freeing Dormin, unaware of the true consequences of your actions. It feels like "forward" is the only way to move because its a video game, so you keep going. The game doesn't hide the wonder of the beasts and the heartbreak in killing them, and you still press on. It's a terrifying message of the dangers of being mislead, and the goal of the main character being to bring back someone dead really helps him feel human. Most know the feeling of wishing a loved one could return, and I'm sure I know people who would try to kill great beasts before accepting the feelings within their heart of loss. The fool is often the easiest to empathize with.

Harrowing stuff! Awesome video game and great music booyah slam dunk.